For what may be obvious reasons, I recently read every story in the original Sherlock Holmes canon — all four novels and 56 short stories.

(This is not bragging. 56 is not that many. Harlan Ellison, one of my favourite writers, is said to have written over 1 000 short stories in his lifetime. You’re welcome to try and verify that claim, but you’ll probably get distracted by the “Controversies and disputes” section of his Wikipedia page.)

The Holmes stories were written before we as a culture fell from god’s grace and invented sequel hooks. As a result, I was struck by the fact that some of the canon’s most famous characters appear quite suddenly and don’t stick around for very long.

An example: if you asked the average person to name three Sherlock Holmes characters, they’d probably say “Holmes, Watson, and Moriarty.” But Professor Moriarty only factors into two stories, and personally appears in just one: "The Final Problem," in which he pops up out of nowhere to kill Holmes. The second story, The Valley of Fear, takes place before "The Final Problem" but was published 21 years later, establishing Moriarty as a recurring threat well after the fact.

Another example: if you asked the average person to name three Sherlock Holmes characters, but stipulated at least one of them had to be a woman, they might say "Holmes, Watson, and Irene Adler." Because Adler is the Woman — the woman who bested Sherlock Holmes.

( spoilers for basically any Sherlock Holmes adaptation that has Irene Adler in it )So it looks like there's going to be a writers' strike in the United States. Among the demands brought forward by the Writer's Guild of America is the regulation of "generative AI" in screenwriting: the use of large language models like GPT, which produce text by calculating where certain words in the English language are statistically most likely to appear next to each other.

No matter what your job is, there's an AI booster out there who thinks GPT can do some part of it better than you can. Those guys are frequently wrong; for example, here's a post by Bret Devereaux examining in-depth the idea that ChatGPT can write your college essays for you. Short answer: it can produce an assemblage of text that looks like an essay, but submitting that text as your essay will not result in a good grade, because a truly successful essay requires a cognitive depth that is completely beyond large language models.

Where ChatGPT and other generative text models like it actually excel is in producing text that meets formulaic requirements in a confident, passable, vaguely novel and blandly inoffensive format.

It is, from a certain point of view, the perfect Hollywood screenwriter.

( Read more... )Also, thanks to the fact that Creative Suite 2 had just become "free," I had access to a pretty powerful video editor for the first time in my life.

All of which led to ... this:

Anyway, the video got privated on one of the occasions Google used their signature move, "Breaking Everyone's Shit." I just got a message on Tumblr asking if I could make it public again, and I couldn't come up with a good enough reason not to.

Looking back, I'm kind of impressed at what I managed to pull off with no training and a few months of downtime.

Also I'm old and have a full-time job now, so don't expect me to do anything like this ever again.

In the original Star Trek series, Klingons were dudes in brownface makeup with a penchant for snakeskin pants and Fu Manchu moustaches. Starting in Star Trek: The Motion Picture and throughout the Star Trek series of the 80s and 90s, the Klingons suddenly had dramatic forehead ridges and dressed like they were headed to a Slipknot concert. In the early 00s, Star Trek: Enterprise started out with the forehead-ridge metalhead Klingons, then had an entire arc that transformed them into the original series’ brownface snakeskin-panted Klingons. Star Trek Into Darkness, which takes place in an alternate-reality version of the original series, kicked that whole thing in the shins with their slightly pointier take on the metalhead Klingons. And then Star Trek: Discovery, which takes place a few years earlier than the original series, slam-dunked Enterprise’s explanation into the trash with its incredibly dramatic take on the Klingons.

Fig 1: 50 years of makeup artists saying "let's get wild."

There are other, smaller incongruities throughout the timeline of the various Star Trek series; for example, Discovery’s holographic communication system is, by official canon, contemporaneous with the original series’ space fax.

Fig 2: equally cutting-edge technology.

There have been attempts to explain these incongruities diegetically; for example, Enterprise’s arc devoted to a gene-altering virus that made the Klingons look the way they did in the original series. Discovery also had some throwaway lines to explain why the holographic communication system disappeared in later shows. But Star Trek didn’t need that and I don’t care.

There are people who will tell you these explanations are vitally important, and every little timeline discrepancy needs to be explained. These people are annoying and you don’t have to listen to them.

Anyway, let’s talk about theater. In live theater, there’s a distinction between the reality the audience observes and the reality the characters experience.

Sometimes this distinction is slight. Julius Caesar probably didn’t speak in iambic pentameter and almost certainly didn’t speak English. Shakespeare doesn’t bother to explain why Caesar does both in the eponymous play; it’s implicitly understood that the characters of Julius Caesar are actually speaking Latin, and the use of English is an interpretive device.

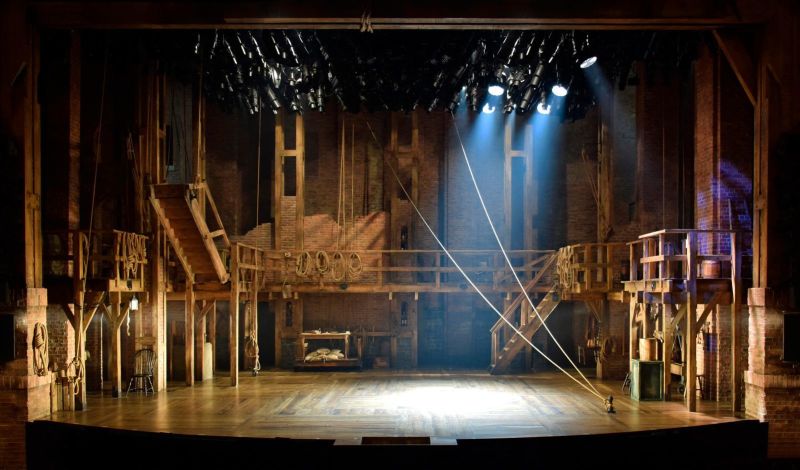

Sometimes the distinction is more blatant. The Broadway production of Hamilton is performed on a bare-bones set featuring a walkway, a couple of staircases, an occasional table, and nothing else. The characters fight on battlefields and walk the streets of 18th century New York, but it’s all implied by their performances; what they see isn’t what we see.

Fig 3: the entire universe, apparently.

This is how I watch Star Trek: with a wall of interpretation between me and the characters. To me, the technological standards and alien makeup change constantly; to the characters, it’s all perfectly consistent. The reality they experience is different than the one I observe. I don’t need anything explained, and whenever Star Trek tries to explain it anyway, all that does is raise even more questions.

The bit from “Trials and Tribble-ations” where Worf gets embarrassed about original series Klingons is good, though. That can stay.

By many accounts, Alexei spent a large part of the work event persuading people to come see Cats. By the end of it, she had two converts: Zach and Kristin.

Kristin seemed fairly excited to watch this trainwreck, while Zach made it clear he was present under duress. However, as showtime loomed ever closer, Zach grew more manic and excited while Kristin had clearly begun to regret her decision.

We got into the theatre and I immediately burst out laughing.

One last straggler wandered in a few minutes before showtime and sat in the very back row, studiously ignoring us.

The movie was indescribable. I, at least, had a baseline understanding of how weird Cats was as a stage show, so I only had to cope with the additional weirdness of the movie. Alexei, Zach, and Kristin had not seen the stage show, so I can't imagine what the movie was like for them. My only hint is this: when Ian McKellen first appeared onscreen, Zach said, very loudly, "oh no."

We got out of the theatre well after midnight, buzzing with delighted, horrified, manic energy. I didn't sleep for hours.

Anyway, that was Cats.

I have no plans to go see Star Wars.

Because the great utopian work of our cultural moment already exists, and it came out 30 years ago.

In 1989, the Cold War was coming to a close. Throughout most of the 20th century, the world had teetered on the precipice of doom: the two most powerful nations in the world possessed, between them, enough firepower to destroy the Earth several times over--and they were at each other’s throats. Then it was over, and despite the fact that the world had failed to physically end, there was still a sense that a kind of apocalypse had occurred. Something had died. Something new was coming.

And on February 17, 1989, Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure was released in theatres.

( Read more... )

- fancy yachts

- Christopher Walken

- extremely tense dinners in public restaurants

- prolonged screaming matches

- huge quantities of wine

- three possible affairs

- a tell-all from a boat captain

- a decades-old DEATH PROPHECY that CAME TRUE

Let's use Avengers: Infinity War as a case study. I, and many other people I've talked to, are absolutely disgusted by Gamora's death in that movie. Not in the Watsonian sense, where they're mad at Thanos for killing her, but in the Doylist sense, where they're mad at the filmmakers for deciding she needed to die and the subtext surrounding her death. Many found the scene's inherent abuse apologia triggering. It broke the movie.

If our culture at large didn't care about ZOMG SPOILERS, then I would have found out about Gamora's death and how she died very shortly after the movie came out. I, and the many people who feel the same way I do, could have saved our $15 and skipped the Infinity War, content to wait and read a recap later.

But of course, that means fewer ticket sales for the studio.

And because Marvel's marketing team berated fans so heavily not to reveal spoilers about the movie, all those people who would've otherwise avoided Infinity War ended up buying those tickets.

There's a good chance Marvel did that on purpose.

Kelly Marcel also wrote the screenplay for the Fifty Shades of Grey movie, which was surprisingly decent compared to the source material. E.L. James actually had her fired because she and the director were making too many (super necessary) changes.

THIS EXPLAINS A LOT.