For what may be obvious reasons, I recently read every story in the original Sherlock Holmes canon — all four novels and 56 short stories.

(This is not bragging. 56 is not that many. Harlan Ellison, one of my favourite writers, is said to have written over 1 000 short stories in his lifetime. You’re welcome to try and verify that claim, but you’ll probably get distracted by the “Controversies and disputes” section of his Wikipedia page.)

The Holmes stories were written before we as a culture fell from god’s grace and invented sequel hooks. As a result, I was struck by the fact that some of the canon’s most famous characters appear quite suddenly and don’t stick around for very long.

An example: if you asked the average person to name three Sherlock Holmes characters, they’d probably say “Holmes, Watson, and Moriarty.” But Professor Moriarty only factors into two stories, and personally appears in just one: "The Final Problem," in which he pops up out of nowhere to kill Holmes. The second story, The Valley of Fear, takes place before "The Final Problem" but was published 21 years later, establishing Moriarty as a recurring threat well after the fact.

Another example: if you asked the average person to name three Sherlock Holmes characters, but stipulated at least one of them had to be a woman, they might say "Holmes, Watson, and Irene Adler." Because Adler is the Woman — the woman who bested Sherlock Holmes.

( spoilers for basically any Sherlock Holmes adaptation that has Irene Adler in it )So it looks like there's going to be a writers' strike in the United States. Among the demands brought forward by the Writer's Guild of America is the regulation of "generative AI" in screenwriting: the use of large language models like GPT, which produce text by calculating where certain words in the English language are statistically most likely to appear next to each other.

No matter what your job is, there's an AI booster out there who thinks GPT can do some part of it better than you can. Those guys are frequently wrong; for example, here's a post by Bret Devereaux examining in-depth the idea that ChatGPT can write your college essays for you. Short answer: it can produce an assemblage of text that looks like an essay, but submitting that text as your essay will not result in a good grade, because a truly successful essay requires a cognitive depth that is completely beyond large language models.

Where ChatGPT and other generative text models like it actually excel is in producing text that meets formulaic requirements in a confident, passable, vaguely novel and blandly inoffensive format.

It is, from a certain point of view, the perfect Hollywood screenwriter.

( Read more... )And in September 2019, Amazon announced a deal with Phoebe Waller-Bridge, who had just swept up six Emmys for the second season of Fleabag. The plan was for Waller-Bridge to collaborate with Donald Glover on a Mr. and Mrs. Smith series, based on the 2005 film. But within a few months, Waller-Bridge departed the show due to clashing creative styles.

This is, by far, the funniest thing to come out of The Hollywood Reporter's article on Amazon Studios. Even funnier than the revelation that their Lord of the Rings show had a 37% domestic completion rate. "Clashing creative styles" is perhaps the mildest way you could phrase what would obviously happen when you put Phoebe Waller-Bridge (granddaughter of an English baronet) in a writers' room with Donald Glover (working-class kid from Atlanta). The only person who might possibly have thought this was a good idea is someone who has heard of both Fleabag and Atlanta but has never watched either and figures they're basically the same thing—i.e. your average Hollywood executive.

This is happening everywhere in media, by the way; Amazon isn't special. Nobody knows what "success" looks like anymore. All the previous methods used to determine what was and was not a successful show no longer apply. So execs just cobble together ideas based on bits and pieces of whatever was popular last year, throw a budget at it, and hope this somehow pays off in the form of a money bin big enough to swim in.

On the creative side, this is a terrific state of affairs if you want to be paid an obscene amount of money for basically no work. If you want to actually make something interesting, you might be out of luck.

First off, while I was previously not at all interested in the Wheel of Time adaptation, I am now very invested in whether it turns out to be any good.

Second, I know Vanyel is Mercedes Lackey's special boy, but I'm not actually sure The Last Herald-Mage is a good place to start with a Valdemar adaptation.

( spoilers for the Arrows and Last Herald-Mage trilogies )

Also, thanks to the fact that Creative Suite 2 had just become "free," I had access to a pretty powerful video editor for the first time in my life.

All of which led to ... this:

Anyway, the video got privated on one of the occasions Google used their signature move, "Breaking Everyone's Shit." I just got a message on Tumblr asking if I could make it public again, and I couldn't come up with a good enough reason not to.

Looking back, I'm kind of impressed at what I managed to pull off with no training and a few months of downtime.

Also I'm old and have a full-time job now, so don't expect me to do anything like this ever again.

In the original Star Trek series, Klingons were dudes in brownface makeup with a penchant for snakeskin pants and Fu Manchu moustaches. Starting in Star Trek: The Motion Picture and throughout the Star Trek series of the 80s and 90s, the Klingons suddenly had dramatic forehead ridges and dressed like they were headed to a Slipknot concert. In the early 00s, Star Trek: Enterprise started out with the forehead-ridge metalhead Klingons, then had an entire arc that transformed them into the original series’ brownface snakeskin-panted Klingons. Star Trek Into Darkness, which takes place in an alternate-reality version of the original series, kicked that whole thing in the shins with their slightly pointier take on the metalhead Klingons. And then Star Trek: Discovery, which takes place a few years earlier than the original series, slam-dunked Enterprise’s explanation into the trash with its incredibly dramatic take on the Klingons.

Fig 1: 50 years of makeup artists saying "let's get wild."

There are other, smaller incongruities throughout the timeline of the various Star Trek series; for example, Discovery’s holographic communication system is, by official canon, contemporaneous with the original series’ space fax.

Fig 2: equally cutting-edge technology.

There have been attempts to explain these incongruities diegetically; for example, Enterprise’s arc devoted to a gene-altering virus that made the Klingons look the way they did in the original series. Discovery also had some throwaway lines to explain why the holographic communication system disappeared in later shows. But Star Trek didn’t need that and I don’t care.

There are people who will tell you these explanations are vitally important, and every little timeline discrepancy needs to be explained. These people are annoying and you don’t have to listen to them.

Anyway, let’s talk about theater. In live theater, there’s a distinction between the reality the audience observes and the reality the characters experience.

Sometimes this distinction is slight. Julius Caesar probably didn’t speak in iambic pentameter and almost certainly didn’t speak English. Shakespeare doesn’t bother to explain why Caesar does both in the eponymous play; it’s implicitly understood that the characters of Julius Caesar are actually speaking Latin, and the use of English is an interpretive device.

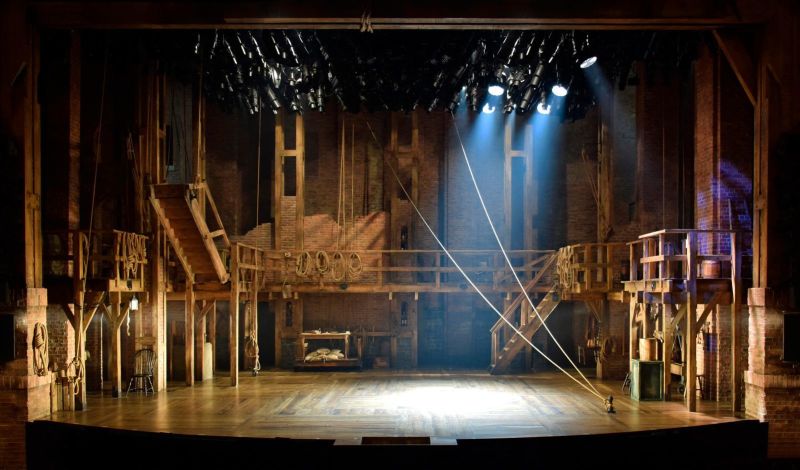

Sometimes the distinction is more blatant. The Broadway production of Hamilton is performed on a bare-bones set featuring a walkway, a couple of staircases, an occasional table, and nothing else. The characters fight on battlefields and walk the streets of 18th century New York, but it’s all implied by their performances; what they see isn’t what we see.

Fig 3: the entire universe, apparently.

This is how I watch Star Trek: with a wall of interpretation between me and the characters. To me, the technological standards and alien makeup change constantly; to the characters, it’s all perfectly consistent. The reality they experience is different than the one I observe. I don’t need anything explained, and whenever Star Trek tries to explain it anyway, all that does is raise even more questions.

The bit from “Trials and Tribble-ations” where Worf gets embarrassed about original series Klingons is good, though. That can stay.

His request for a list resulted in the creation of a spreadsheet.

A group of us have been watching episodes three times a week, over lunch, and Kyle's reviews are one of the few things keeping me sane. With his permission, here's his reviews of the Original Series episodes we watched.

( spoilers for a 60-year-old show )

Go follow Kyle on the bird website.

I was trying to track down a source for a piece of writing advice I once read, which described a phenomenon called "California conversation." Unfortunately, the phrase "California conversation" only turns up election articles, no matter how much I refine my search terms. I'm in hell.

Anyway, from what I recall, "California conversation" refers to dialogue that fails to realistically reserve emotion and/or pain. Characters will, while talking to people they barely know, go into incredible detail about their feelings and tragic backstories. To paraphrase the source that I still can't find, those who write California conversations claim "that's how real people talk," and that's true--but only in California, where everyone desperately wants to seem interesting.

You'll find a lot of California conversation in television these days. TV writers have started to realize the things they put their characters through are traumatic and emotionally fraught, but they also work in an era of storytelling where Plot reigns supreme. Emotional arcs are for girls and themes are for 8th grade book reports; all that's important is outsmarting the Reddit theorists. Therefore, any emotional processing has to happen during incredibly short scenes set aside specifically for that purpose.

And because these scenes are so short, what we get is a brief exchange where a character talks about how they feel bad in the most explicit way possible, nothing is resolved, and the story quickly steers back toward the all-important, convoluted Plot. Because the showrunner wants you to know he's smarter than you.

I'm sure everybody who knows me is sick of hearing me talk about Leverage, but this is something Leverage avoided quite well. Because each season's metaplot was usually kept on the backburner, individual episodes were free to tie into the characters' emotional development. A character was able to process their scars and the changes in their lives by resolving the episode's plot.

As a result, dialogue was often multi-layered, with characters hashing out both the case of the week and their feelings about it. But the feelings were in the subtext and the actors' performance, where they belonged.

Of course, we also live in an era of storytelling where actors aren't told what scenes they're filming, so I guess it would be difficult to get a nuanced, multilayered performance out of anyone these days.

In summary, Damon Lindelof should be tried at the Hague.