So. Klingons.

In the original Star Trek series, Klingons were dudes in brownface makeup with a penchant for snakeskin pants and Fu Manchu moustaches. Starting in Star Trek: The Motion Picture and throughout the Star Trek series of the 80s and 90s, the Klingons suddenly had dramatic forehead ridges and dressed like they were headed to a Slipknot concert. In the early 00s, Star Trek: Enterprise started out with the forehead-ridge metalhead Klingons, then had an entire arc that transformed them into the original series’ brownface snakeskin-panted Klingons. Star Trek Into Darkness, which takes place in an alternate-reality version of the original series, kicked that whole thing in the shins with their slightly pointier take on the metalhead Klingons. And then Star Trek: Discovery, which takes place a few years earlier than the original series, slam-dunked Enterprise’s explanation into the trash with its incredibly dramatic take on the Klingons.

Fig 1: 50 years of makeup artists saying "let's get wild."

There are other, smaller incongruities throughout the timeline of the various Star Trek series; for example, Discovery’s holographic communication system is, by official canon, contemporaneous with the original series’ space fax.

Fig 2: equally cutting-edge technology.

The non-diegetic explanation for these things is obvious: Star Trek is a show about the future, and nothing dates faster than the future. On top of that, each successive production had a higher budget, access to improved effects tech, and artists who leveraged both to try out some Stuff.

There have been attempts to explain these incongruities diegetically; for example, Enterprise’s arc devoted to a gene-altering virus that made the Klingons look the way they did in the original series. Discovery also had some throwaway lines to explain why the holographic communication system disappeared in later shows. But Star Trek didn’t need that and I don’t care.

There are people who will tell you these explanations are vitally important, and every little timeline discrepancy needs to be explained. These people are annoying and you don’t have to listen to them.

Anyway, let’s talk about theater. In live theater, there’s a distinction between the reality the audience observes and the reality the characters experience.

Sometimes this distinction is slight. Julius Caesar probably didn’t speak in iambic pentameter and almost certainly didn’t speak English. Shakespeare doesn’t bother to explain why Caesar does both in the eponymous play; it’s implicitly understood that the characters of Julius Caesar are actually speaking Latin, and the use of English is an interpretive device.

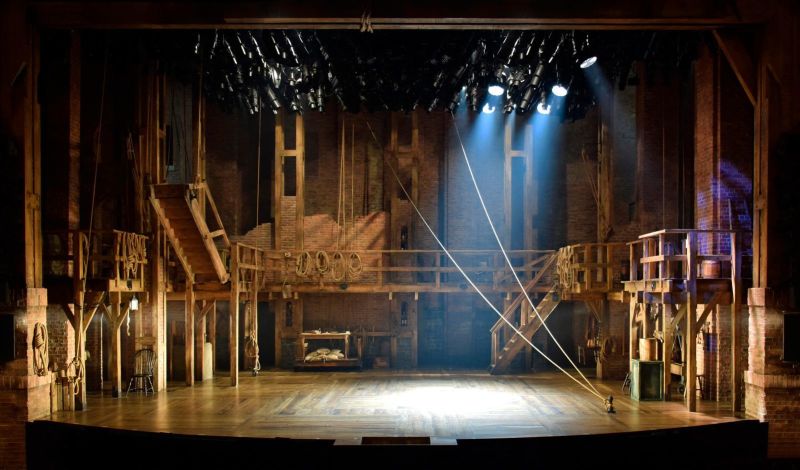

Sometimes the distinction is more blatant. The Broadway production of Hamilton is performed on a bare-bones set featuring a walkway, a couple of staircases, an occasional table, and nothing else. The characters fight on battlefields and walk the streets of 18th century New York, but it’s all implied by their performances; what they see isn’t what we see.

Fig 3: the entire universe, apparently.

This is how I watch Star Trek: with a wall of interpretation between me and the characters. To me, the technological standards and alien makeup change constantly; to the characters, it’s all perfectly consistent. The reality they experience is different than the one I observe. I don’t need anything explained, and whenever Star Trek tries to explain it anyway, all that does is raise even more questions.

The bit from “Trials and Tribble-ations” where Worf gets embarrassed about original series Klingons is good, though. That can stay.

In the original Star Trek series, Klingons were dudes in brownface makeup with a penchant for snakeskin pants and Fu Manchu moustaches. Starting in Star Trek: The Motion Picture and throughout the Star Trek series of the 80s and 90s, the Klingons suddenly had dramatic forehead ridges and dressed like they were headed to a Slipknot concert. In the early 00s, Star Trek: Enterprise started out with the forehead-ridge metalhead Klingons, then had an entire arc that transformed them into the original series’ brownface snakeskin-panted Klingons. Star Trek Into Darkness, which takes place in an alternate-reality version of the original series, kicked that whole thing in the shins with their slightly pointier take on the metalhead Klingons. And then Star Trek: Discovery, which takes place a few years earlier than the original series, slam-dunked Enterprise’s explanation into the trash with its incredibly dramatic take on the Klingons.

Fig 1: 50 years of makeup artists saying "let's get wild."

There are other, smaller incongruities throughout the timeline of the various Star Trek series; for example, Discovery’s holographic communication system is, by official canon, contemporaneous with the original series’ space fax.

Fig 2: equally cutting-edge technology.

There have been attempts to explain these incongruities diegetically; for example, Enterprise’s arc devoted to a gene-altering virus that made the Klingons look the way they did in the original series. Discovery also had some throwaway lines to explain why the holographic communication system disappeared in later shows. But Star Trek didn’t need that and I don’t care.

There are people who will tell you these explanations are vitally important, and every little timeline discrepancy needs to be explained. These people are annoying and you don’t have to listen to them.

Anyway, let’s talk about theater. In live theater, there’s a distinction between the reality the audience observes and the reality the characters experience.

Sometimes this distinction is slight. Julius Caesar probably didn’t speak in iambic pentameter and almost certainly didn’t speak English. Shakespeare doesn’t bother to explain why Caesar does both in the eponymous play; it’s implicitly understood that the characters of Julius Caesar are actually speaking Latin, and the use of English is an interpretive device.

Sometimes the distinction is more blatant. The Broadway production of Hamilton is performed on a bare-bones set featuring a walkway, a couple of staircases, an occasional table, and nothing else. The characters fight on battlefields and walk the streets of 18th century New York, but it’s all implied by their performances; what they see isn’t what we see.

Fig 3: the entire universe, apparently.

This is how I watch Star Trek: with a wall of interpretation between me and the characters. To me, the technological standards and alien makeup change constantly; to the characters, it’s all perfectly consistent. The reality they experience is different than the one I observe. I don’t need anything explained, and whenever Star Trek tries to explain it anyway, all that does is raise even more questions.

The bit from “Trials and Tribble-ations” where Worf gets embarrassed about original series Klingons is good, though. That can stay.

tags: